Mr. Market Miscalculates - Howard Marks

Tan KW

Publish date: Fri, 23 Aug 2024, 07:15 AM

In his book The Intelligent Investor, first published in 1949, Benjamin Graham, who was Warren Buffett’s teacher at Columbia Business School, introduced a fellow he called Mr. Market:

Imagine that in some private business you own a small share that cost you $1,000. One of your partners, named Mr. Market, is very obliging indeed. Every day he tells you what he thinks your interest is worth and furthermore offers either to buy you out or to sell you an additional interest on that basis. Sometimes his idea of value appears plausible and justified by business developments and prospects as you know them. Often, on the other hand, Mr. Market lets his enthusiasm or his fears run away with him, and the value he proposes seems to you a little short of silly.

Of course, Graham intended Mr. Market as a metaphor for the market as a whole. Given Mr. Market’s inconsistent behavior, the prices he assigns to stocks each day can diverge – sometimes wildly – from their fair value. When he’s overenthusiastic, you can sell to him at prices that are intrinsically too high. And when he’s overly fearful, you can buy from him at prices that are fundamentally too low. Thus, his miscalculations provide profit opportunities to investors interested in taking advantage of them.

* * *

There’s a great deal to be said about investors’ foibles, and I’ve shared much of it over the years. But the rapid market decline we saw in the first week of August – along with the rapid rebound – compels me to pull together what I’ve said previously on the subject, along with some priceless investing cartoons from my collection, and add a few new observations.

To set the scene, let’s review recent events. As a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, soaring inflation, and the U.S. Federal Reserve’s rapid interest rate increases, 2022 was one of the worst years ever for the combination of stocks and bonds. Sentiment reached its low around the middle of 2022, with investors depressed by the universally negative outlook: “We have inflation, and that’s bad. And the rate increases to fight it are sure to bring on a recession, and that’s bad.” Investors could think of few positives.

Then the mood lightened and, late in 2022, investors coalesced around a positive narrative: the slow economic growth would cause inflation to decline, and that would permit the Fed to start lowering rates in 2023, leading to economic vigor and market gains. A significant stock market rally began and continued nearly uninterrupted until this month. Although the rate cuts anticipated in 2022 and 2023 still haven’t materialized, optimism has been in the ascendency in the stock market. The S&P 500 stock index rose by 54% (not counting dividends) in the 21 months which ended on July 31, 2024. That day, Fed Chair Jerome Powell confirmed that the Fed was moving closer to a rate cut, and things appeared to be on track for economic growth and further stock market appreciation.

But that same day, the Bank of Japan announced its biggest increase in its short-term interest rate in over 17 years (to a whopping 0.25%!). This shocked the Japanese stock market, to which people had been warming for over a year. In addition, and importantly, the announcement played havoc with investors who had engaged in “the carry trade.” For years, Japan’s infinitesimal – and often negative – interest rates have meant that people could borrow cheaply in Japan and invest the borrowed funds in any number of assets, there and elsewhere, that promised to return more, for a “positive carry” (aka “free money”). This led to the establishment of highly levered positions. It seems odd that a quarter-point increase in interest rates could require some of these positions to be unwound. But it did, leading to motivated selling in a variety of asset classes as those who had engaged in the practice moved to cut their leverage.

Starting the next day, the U.S. announced mixed economic news. On August 1, we learned that the Manufacturing Purchasing Managers’ Index had dipped and initial jobless claims had risen. On the other hand, corporate profit margins continued to look good, and gains in productivity surprised to the upside. A day later, we learned that employment gains had moderated, with hiring rising less than had been expected. The unemployment rate stood at 4.3% at the end of July, up from a low of 3.4% in April 2023. This was still very low by historical standards, but, according to the suddenly popular “Sahm Rule” (don’t complain to me; I’d never heard of it either), since 1970, an increase in the three-month average unemployment rate of 0.5 percentage points or more from the low of the prior 12 months has never occurred without the economy already being in recession. Around the same time, Warren Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway announced that it had sold off a good part of its massive holding of Apple shares.

In all, this news constituted a triple whammy. The resulting flip-flop from optimism to pessimism set off a significant stock market rout. The S&P 500 fell on three consecutive trading days – August 1, 2, and 5 – by a total of 6.1%. The replay of the mistakes I’ve witnessed for decades was so obvious that I can’t resist cataloging them below.

What’s Behind the Market’s Volatility?

On the first two days of August, I was in Brazil, where people often asked me to explain the sudden collapse. I referred them to my 2016 memo On the Couch. Its key observation was that in the real world, things fluctuate between ‘pretty good’ and ‘not so hot,’ but in investing, perception often swings from ‘flawless’ to ‘hopeless.’ That says about 80% of what you need to know on the subject.

If reality changes so little, why do estimates of value (that’s what security prices are supposed to be) change so much? The answer has a lot to do with changes in mood. As I wrote over 33 years ago, in only my second memo:

The mood swings of the securities markets resemble the movement of a pendulum. . . . between euphoria and depression, between celebrating positive developments and obsessing over negatives, and thus between overpriced and underpriced. This oscillation is one of the most dependable features of the investment world, and investor psychology seems to spend much more time at the extremes than it does at a “happy medium.” (First Quarter Performance, April 1991)

Mood swings do a lot to alter investors’ perception of events, causing prices to fluctuate madly. When prices collapse as they did at the start of this month, it’s not because conditions have suddenly become bad. Rather, they become perceived as bad. Several factors contribute to this process:

-

heightened awareness of things on one side of the emotional ledger,

-

a tendency to overlook things on the other side, and

-

similarly, a tendency to interpret things in a way that fits the prevailing narrative.

What this means is that in good times, investors obsess about the positives, ignore the negatives, and interpret things favorably. Then, when the pendulum swings, they do the opposite, with dramatic effects.

One important idea underpinning economics is the theory of rational expectations, described by Investopedia as follows:

The rational expectations theory . . . posits that individuals base their decisions on three primary factors: their human rationality, the information available to them, and their past experiences.

If security prices were really the result of the rational, dispassionate evaluation of data, presumably one piece of negative information would move the market down a little, and the next such piece would move it down a bit more, and so forth. But instead, we see that an optimistic market is capable of ignoring individual pieces of bad news until a critical mass of bad news builds up, at which time a tipping point is reached, the optimists surrender, and a rout begins. Rudiger Dornbush’s great quote about economics is highly applicable here: “. . . things take longer to happen than you think they will, and then they happen faster than you thought they could.” Or as my partner Sheldon Stone says, “The air goes out of the balloon much faster than it went in.”

The non-linear nature of this process suggests something very different from rationality is at work. In particular, as in many other aspects of life, cognitive dissonance plays a big part in investors’ psyches. The human brain is wired to ignore or reject incoming data that is at odds with prior beliefs, and investors are particularly good at this.

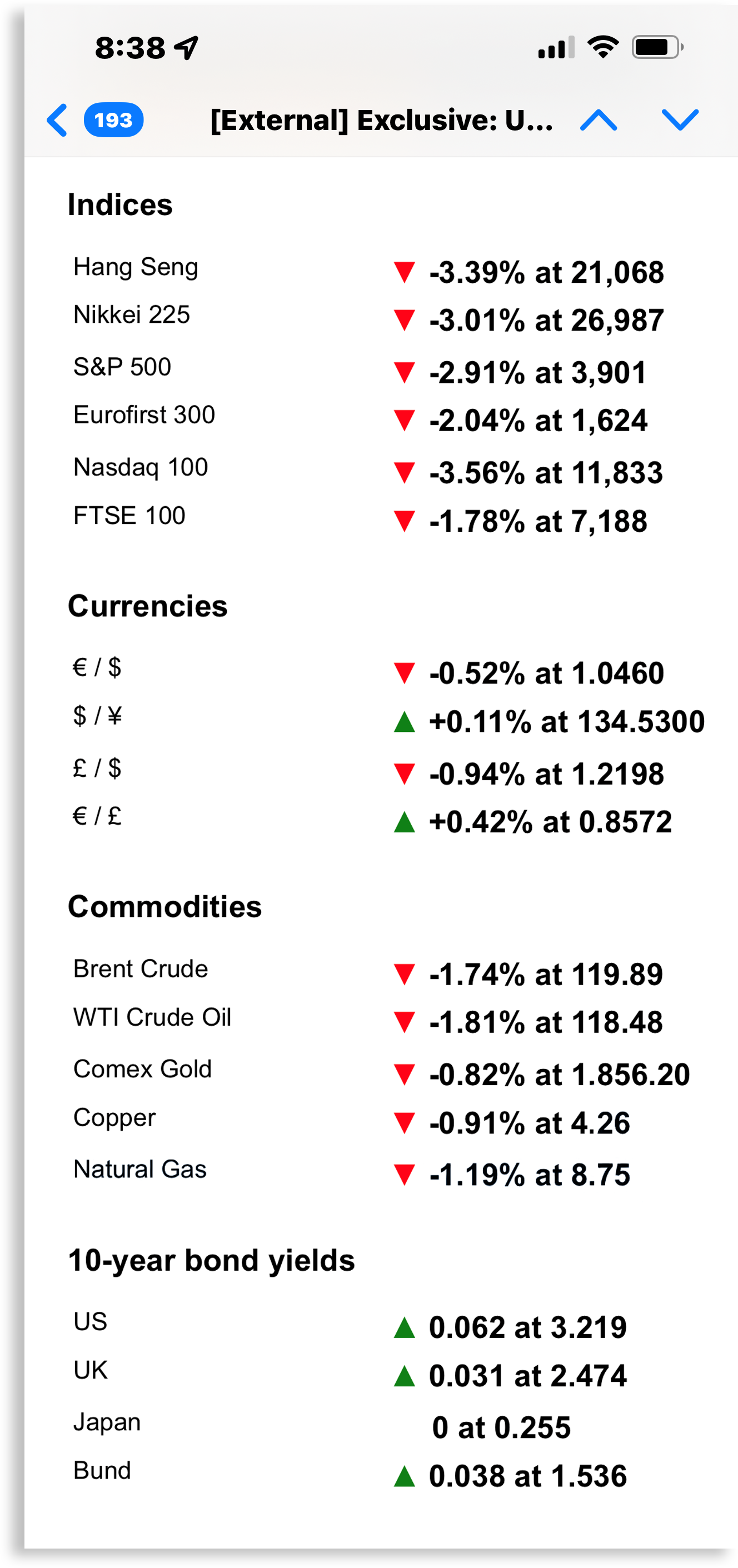

While we’re on the subject of irrationality, I’ve been waiting for an opportunity to share the following screenshot from June 13, 2022:

This was a tough day in the markets: interest rates were rising thanks to the actions of the Fed and other central banks, and asset prices were under significant pressure as a result. But take a look at the table. Every country’s equity index was down significantly. Every currency was down relative to the dollar. Every commodity was down. Only one thing was up: bond yields . . . meaning bond prices were down, too. Wasn’t there one asset or country whose value didn’t decline that day? What about gold, which is supposed to do well in difficult times? My point here is that, during big market moves, no one performs rational analysis or makes distinctions. They just throw out the baby with the bathwater, primarily because of psychological swings. As the old saying goes, “in times of crisis, all correlations go to 1.”

Further, the data in the table exhibit an additional phenomenon that’s often present during extreme moves: contagion. Something goes wrong in the U.S. market. European investors take that as a sign of trouble, so they sell. Asian investors detect that something negative is afoot, so they sell overnight. And when U.S. investors come in the next morning, they’re spooked by the negative developments in Asia, which confirm their pessimistic inclinations, so they sell. This is a lot like the game of telephone we played when I was little: the message may be miscommunicated as it’s passed down the chain, but it still encourages ill-founded actions.

When psychology is swinging radically, meaningless statements can be given weight. Thus, during the three-day decline earlier this month, it was observed that foreigners sold more Japanese stocks than they bought, and investors reacted as if this meant something. But if foreigners sold on balance, Japanese investors must have bought on balance. Should either of these phenomena be treated as more significant than the other? If so, which one?

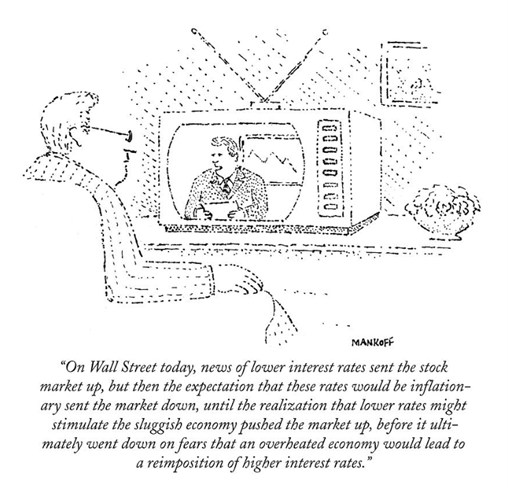

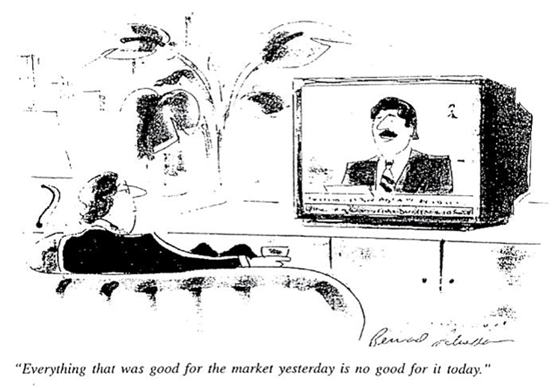

Further complicating things in terms of rational analysis is the fact that most developments in the investment world can be interpreted both positively and negatively, depending on the prevailing mood.

Another classic cartoon sums up this ambiguity in fewer words. It’s highly applicable to the market tremor that inspired this memo.

One more source of miscalculation is investors’ tendency toward optimism and wishful thinking. Investors in general – and equity investors in particular – must, by definition, be optimists. Who other than people with positive expectations (and/or a strong desire for increased wealth) would be willing to part with money today based on the possibility of getting back more in the future?

Charlie Munger, Warren Buffett’s late partner, routinely quoted the ancient Greek statesman Demosthenes, who said, “Nothing is easier than self-deceit. For what each man wishes, that he also believes to be true.” One great example is “Goldilocks thinking”: the belief that the economy will be neither strong enough to bring on inflation nor weak enough to lapse into recession. Things sometimes work out that way – as may be the case right now – but not nearly as often as investors posit. Expectations that incline toward the positive encourage aggressive behavior on the part of investors. And if this behavior is rewarded in good times, still more aggressiveness usually ensues. Rarely do investors realize that (a) there can be a limit to the run of good news or (b) an upswing can be so strong as to be excessive, rendering a downswing inevitable.

For years, I quoted Buffett as having warned investors to temper their enthusiasm: “When investors lose track of the fact that corporate profits grow at 7% on average, they tend to get into trouble.” In other words, if corporate profit growth averages 7%, shouldn’t investors begin to worry if stocks appreciate by 20% a year for a while (as they did throughout the 1990s)? I thought it was such a good quote that I asked Buffett when he said it. Unfortunately, he answered that he hadn’t. But I still think it’s an important warning.

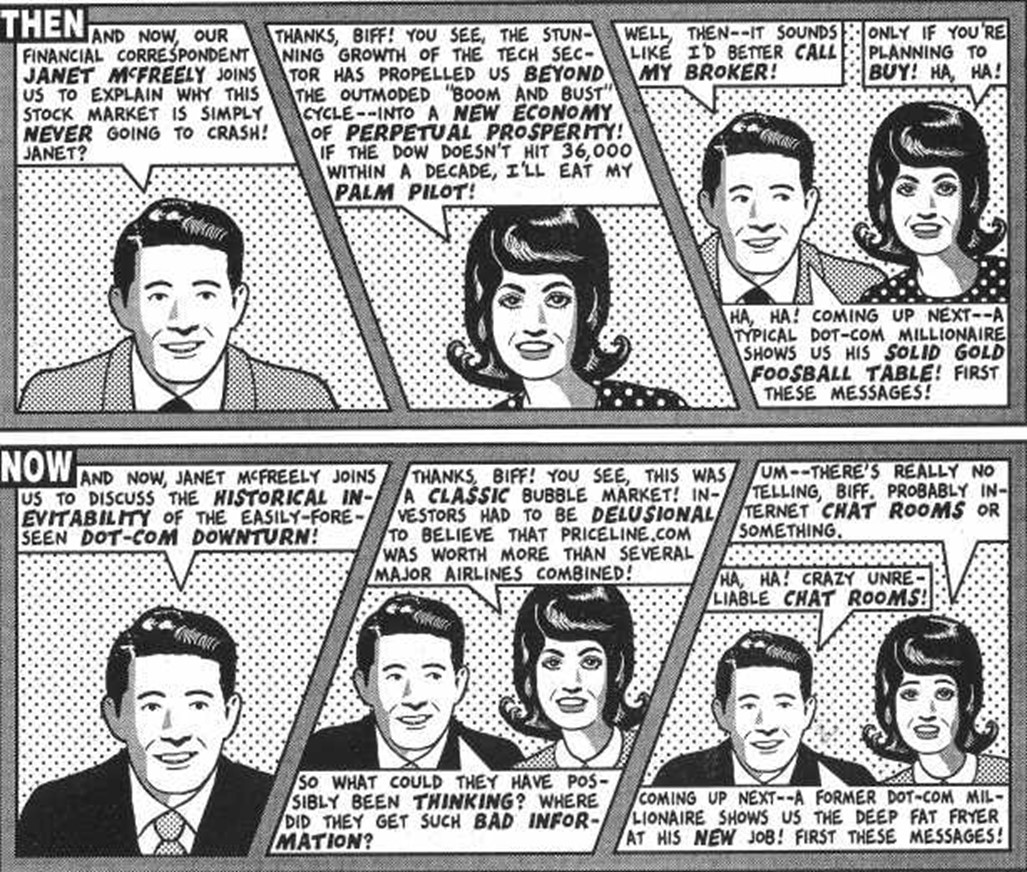

That inaccurate recollection reminds me of John Kenneth Galbraith’s trenchant reference to one of the most important causes of financial euphoria: “the extreme brevity of the financial memory.” It’s this trait that allows optimistic investors to engage in aggressive behavior, untroubled by knowledge of what such behavior led to in the past. Further, it makes it easy for investors to forget past errors and invest blithely on the basis of the newest miraculous development.

Finally, the investment world might be less unstable if there were immutable rules – like the one governing gravity – that could be counted on to always produce the same results. But there are no such rules, since markets aren’t built on natural laws, but rather the shifting sands of investor psychology.

For example, there’s a long-running adage that says we should “buy on rumor and sell on news.” That is, the introduction of favorable expectations is a buy signal, because expectations often continue to rise. That ends when the news arrives, however, because the impetus for gains has been realized and no further good news remains to take the market higher. But in the carefree environment of a month ago, I told my partner Bruce Karsh that maybe the prevailing attitude had become “buy on rumor and buy on news.” In other words, investors were acting as though it was always a good time to buy. Rationally, one shouldn’t price in the possibility of a favorable event twice: both when the possibility of the event is introduced and when the event occurs. But euphoria can get the better of people.

Another example of the absence of meaningful guidelines can be seen in this excerpt from one of the oldest clippings in my file:

A continuing pattern of consolidation and group rotation suggests that increasing emphasis should be placed on buying stocks on relative weakness and selling them on relative strength. This would be a marked contrast to some earlier periods where emphasizing relative strength proved to be effective. (Loeb, Rhoades & Co., 1976)

In short, sometimes the things that have gone up the most should be expected to continue to go up the most, and sometimes the things that have gone up the least should be expected to go up the most. To which many of you might respond “duh.” Bottom line: there are few effective rules for investors to follow. Superior investing always comes down to skillful analysis and superior insight, not adherence to formulas and guidelines.

* * *

Volatile psychology, skewed perception, overreaction, cognitive dissonance, rapid-fire contagion, irrationality, wishful thinking, forgetfulness, and the lack of dependable principles. That’s quite a laundry list of ills. Together, they constitute the main cause of extreme market highs and lows and are responsible for the volatile swings between them. Ben Graham said that, in the long run, the market is a weighing machine that assesses the merit of each asset and assigns an appropriate price. But in the short term, it’s merely a voting machine, and the investor sentiment that moves it swings wildly, incorporating little rationality and assigning daily prices that often reflect little in terms of intelligence.

Rather than try to reinvent the wheel, I’ll repeat some of what I’ve said in two past memos:

Especially during downdrafts, many investors impute intelligence to the market and look to it to tell them what’s going on and what to do about it. This is one of the biggest mistakes you can make. As Ben Graham pointed out, the day-to-day market isn’t a fundamental analyst; it’s a barometer of investor sentiment. You just can’t take it too seriously. Market participants have limited insight into what’s really happening in terms of fundamentals, and any intelligence that could be behind their buys and sells is obscured by their emotional swings. It would be wrong to interpret the recent worldwide drop as meaning the market “knows” tough times lay ahead. (It’s Not Easy, September 2015)

My bottom line is that markets don’t assess intrinsic value from day to day, and certainly they don’t do a good job during crises. Thus, market price movements don’t say much about fundamentals. Even in the best of times, when investors are driven by fundamentals rather than psychology, markets show what the participants think value is, rather than what value really is. Value is something the market doesn’t know any more about than the average investor. And advice from the average investor obviously can’t help you be an above average investor.

Fundamentals – the outlook for an economy, company or asset – don’t change much from day to day. As a result, daily price changes are mostly about (a) changes in market psychology and thus (b) changes in who wants to own something or un-own something. These two statements become increasingly valid the more daily prices fluctuate. Big fluctuations show that psychology is changing radically. (What Does the Market Know?, January 2016)

The market fluctuates at the whim of its most volatile participants: those who are willing (a) to buy at a big premium to the former price when the news is good and enthusiasm is riding high and (b) to sell at a big discount from the former price when the news is bad and pessimism is rampant. Thus, as I wrote in On the Couch, every once in a while, the market needs a trip to the shrink.

It’s important to note that, as my partner John Frank points out, in comparison to the total number who own each company, it takes relatively few people to drive prices up during bubbles or down during crashes. When shares in a company that was worth $10 billion a month ago trade at prices implying a valuation of $12 billion or $8 billion, it doesn’t mean the whole company would change hands at these prices; just a tiny sliver. Regardless, a few emotional investors can move prices much more than should be the case.

The worst thing you can do is join in when other investors go off on these irrational jags. It’s far better to watch with bemusement from the sidelines, buttressed by an understanding of how markets work. But better still to see Mr. Market’s overreactions for what they are and accommodate him, selling to him when he’s eager to buy regardless of how high the price is, and buying from him when he desperately wants out. Here’s how Ben Graham followed the introduction of Mr. Market that I included on page 1:

If you are a prudent investor or a sensible businessman will you let Mr. Market’s daily communication determine your view of the value of your $1,000 interest in the enterprise? Only in case you agree with him, or in case you want to trade with him. You may be happy to sell out to him when he quotes you a ridiculously high price, and equally happy to buy from him when his price is low. But the rest of the time you will be wiser to form your own ideas of the value of your holdings, based on full reports from the company about its operations and financial position.

In other words, it’s the primary job of the investor to take note when prices stray from intrinsic value and figure out how to act in response. Emotion? No. Analysis? Yes.

August 22, 2024

https://www.oaktreecapital.com/insights/memo/mr-market-miscalculates

More articles on Gurus

Created by Tan KW | Oct 23, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Oct 17, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Aug 27, 2024

Created by Tan KW | Jun 26, 2024

Created by Tan KW | May 05, 2024